Arizona’s Legislative Push to Enhance Local Cooperation with ICE

In recent months, the Trump administration has intensified its efforts to engage local law enforcement in the mass deportation initiative. Arizona is witnessing a legislative drive to increase local law enforcement’s collaboration with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Currently, Arizona has only a few agencies officially allied with the federal government for immigration enforcement. However, Republican lawmakers are advocating for new laws to encourage greater cooperation with ICE.

Senate President Warren Petersen introduced the Arizona ICE Act, which aims to prohibit local governments from setting rules against federal immigration cooperation. It also mandates local sheriffs and state prison officials to detain individuals in their custody upon ICE’s request.

Petersen stated, “If you have been arrested and you are in prison, they must hold you for 48 hours, so you can be turned over to ICE.” Initially, Petersen’s proposal included a requirement for local law enforcement to enter into 287-g agreements, granting them specific permissions to engage in immigration activities. However, facing opposition from sheriffs, this mandate was removed from the legislation.

The Arizona Sheriffs Association, under the leadership of Yavapai County Sheriff David Rhodes, has expressed support for the bill. He commented, “It simply prohibits local governments and officials from making policies that would restrict government officials of course, but in law enforcement’s case, the ability to keep communities safe.”

Petersen’s proposal is one of several Republican legislative efforts aimed at obligating state agencies to support ICE in detaining, housing, or deporting immigrants without legal status. Other proposals include requiring the governor and Attorney General’s Office to cooperate with ICE and permitting ICE to use a closed state prison for housing detainees.

Although Governor Katie Hobbs may veto these measures, Petersen has considered putting his bill to a public vote, referencing a previous voter-approved border measure that Hobbs vetoed.

Pinal County Sheriff Ross Teeple, who has had a 287-g agreement since 2008, described the process in his county. When individuals are booked into county jail on state charges, trained 287-g personnel check federal databases for deportation orders or warrants. Teeple noted, “At some point during their incarceration, one of my trained 287-g employees is going to run that individual through a federal database to find out if they have a deportation order, an ICE warrant for their arrest, or any other federal warrant for their arrest.”

ICE then has 72 hours to take custody of the individual. In 2022, 41 non-citizens detained in Pinal County were referred to federal authorities.

While Teeple supports the program in his county, he opposes imposing it on others. “As a 287-g agency, I do not like any state law that requires sheriffs to do something that’s an unfunded mandate or may not be best for their county,” he said. He did not support the original mandate to enforce 287-g agreements across localities.

The revised Arizona ICE Act allows local and state entities to partner with federal agencies like the Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security in enforcing immigration laws. It also tasks the Attorney General’s Office with investigating areas obstructing federal immigration efforts.

Jason Houser, once the ICE chief of staff under President Joe Biden, remarked that the legislation aligns with federal goals to broaden deportation efforts. He noted, “So clearly somebody realized after reading the limitations of 287-g, it’s really not that helpful, if you’re really trying to operationalize mass removal and detention.”

Houser highlighted the training time for local 287-g officers and the uncertainty of a detainee’s deportability. “They then are bonded out, and then an officer just spent two days doing that instead of targeting some drug cartel member,” he explained.

While local jurisdictions remain part of broader deportation strategies, Houser expects new policies involving agencies like the U.S. Border Patrol or the Justice Department. He believes the focus on 287-g agreements misses the larger federal shift in immigration policy.

“They are changing the paradigm of how they’re going after and inflicting these new policies, and how they want to get to 1 million removals,” he stated.

The Trump administration has utilized statutes such as the Alien Enemies Act to deport individuals, including hundreds of Venezuelans to El Salvador despite legal challenges. A 60 Minutes report highlighted that 75% of the 238 Venezuelan men deported in March had no criminal records.

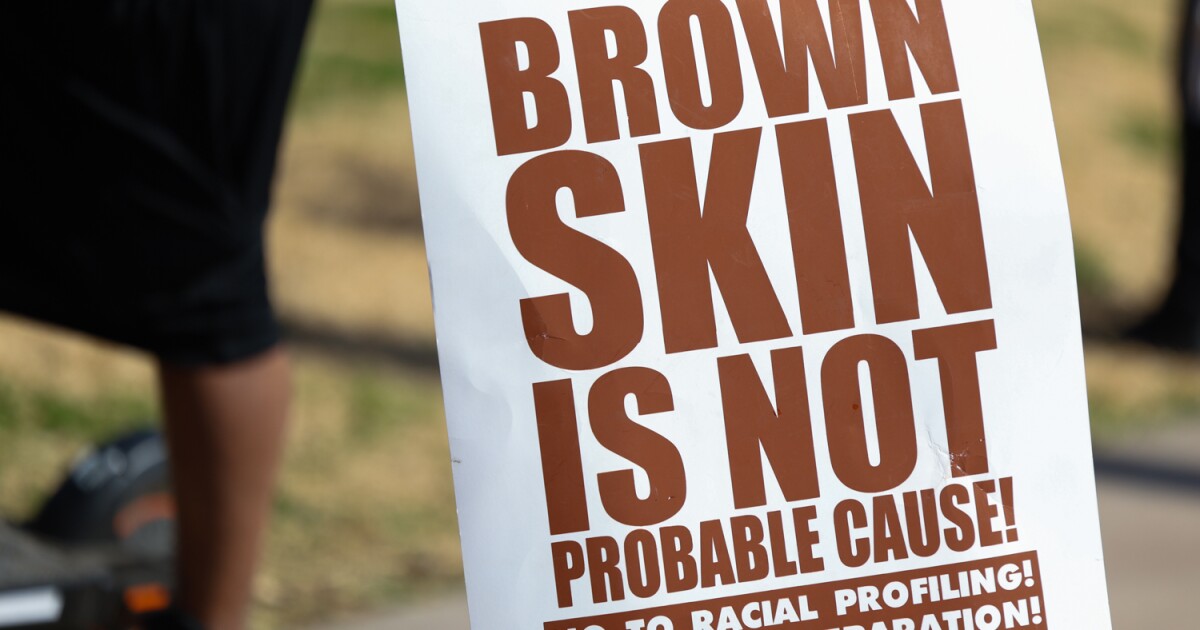

Rocky Rivera, a Tucson-based activist with Living United for Change in Arizona (LUCHA), has personal experiences with federal scrutiny. Despite being a U.S. citizen born in Bisbee with a veteran father, Rivera recalls an incident from 2008 when his father, undergoing cancer treatment, was profiled by a deputy asking about their citizenship status.

Rivera recounted, “All he did was ask the young sheriff if he was a citizen himself, he said, ‘are you?’ And right then, the whole situation escalated, he got put in handcuffs.” A Border Patrol agent eventually recognized his father, illustrating the potential for profiling.

Rivera anticipates that current legislative efforts may lead to similar situations, stating, “This does give them the right to race profile us. There’s no way around it. They’re going to do it again.” The Arizona ICE Act has advanced through the Legislature with Republican support and awaits consideration in the Arizona House of Representatives.

This is Part 2 of a two-part series looking at the Arizona Legislature’s efforts to increase local involvement in immigration enforcement. Read Part 1 here.